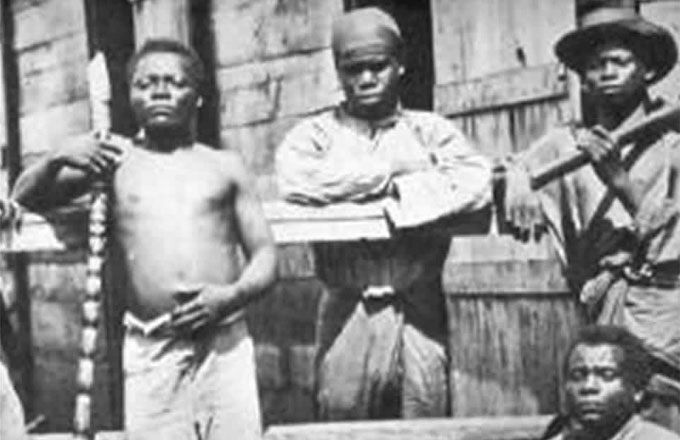

The recruits in the French Antilles.

Employment contracts were first a matter of private law before being regulated by the royal administration in the 17th and 18th centuries. We see them reappear in the 19th century, from the Restoration, and more particularly under the Second Empire and at the beginning of the Ille République.

Engaged: as part of immigration to the islands, people who arrived with an employment contract. Despite the permanence of the unequal contract, usage generally reserves this qualification for Europeans who arrived in the 17th and 18th centuries. Then, more than committed, we will talk about Madeirans, Hindus or Coolies, Chinese, Congos …, other unequal names applied to foreigners whose descendants will take time to be recognized as Creole.

“Pledged people”: individuals who have signed a pact with the devil. Ruthless, popular wisdom still expresses the idea of an unequal contract. In the first case, the committed risks his body, in the second, his soul. Was hope so absent from the condition of entry?

To provide some elements of response to this question, while conducting some brief comparisons with the 19th century, we will focus the debate on those engaged in the 17th and 18th centuries, looking for elements of evolution, and with a particular emphasis on the Martinican framework.

Engaged or temporary slaves?

Perpetual slavery or temporary slavery? The debate, which started in the 17th century, continued in the 18th and reappeared in the 19th century. The participant knowing that his fate is temporary, it all depends on the percentage of chances he has of leaving it alive.

In 1786, in the Annals of the Sovereign Council, at a time when there were still white servants, but no longer engaged, P. F. R. Des-Salles gave us an a posteriori vision: “They were, for the inhabitants of that time, what are, and have always been, the negroes of all times: they rolled with the slaves, and, except for the punishments, were treated like them (…)”.

Father Du Tertre, who knew them well, strongly denounced the fate which was done to them in the first years of the colonization of Guadeloupe in his General History of the Antilles inhabited by the French: “For although these poor committed (…) were extraordinarily weakened by misery and hunger, they were treated worse than slaves, and they were only pushed to work with sticks and halberds , so that some who had been captive in Barbary, cursed the hour that they had come out of it, publicly invoking the devil, and giving themselves to him, provided that he carried them back to France; and what’s more horrible, some are dead, with these words in their mouths. ”

“The harshness with which most treat the hired French who they bought to serve them for three years, is the only thing that seems unfortunate to me; for they make them work with excess, they feed them very badly, and often compel them to work in the company of their slaves, which afflicts these poor people more than the excessive pains they suffer. There were once masters so cruel that we had to forbid them to ever buy them, and I knew one who buried more than 50 in the square, whom he had killed by force to make them work, and for not having assisted them in their illnesses. This hardness undoubtedly comes from the fact that they only have them for three years, which means that they are more careful to spare the Negroes than these poor people; but the charity of the governors has greatly softened their condition by the ordinances which they have made in their favor. ”

In the 19th century, from the Restoration, the commitment was reborn with, for example, Madeirans. In the second half of the century, the massive resumption of engagement with blacks and Asians by both France and England took place within a legal framework both national and international. However, in spite of the precautions taken because of the condemnation of slavery by the European nations, the engagement raises, under the Third Republic, a debate centered on the human rights that an article published by Sch ÷ lcher in 1885 in the Moniteur des Colonies, and taken up in Colonial Polemic, allows us to summarize:

“Outside ordinary law, everything is arbitrary, it is the organized disorder of good pleasure and individual freedom has no guarantee. (…) The current immigrant, in fact, is not a man with civil rights, he is reduced to the state of a minor who can do nothing by himself; the trustees, who fulfill the role of tutor for him, act in all circumstances for him; he does not discuss the conditions of his engagement, they are decided between the administration and the planter whom he does not know and to whom we deliver him when he disembarks. Minor, is he malnourished, badly dressed, mistreated, beaten, he does not have the right to file a complaint before the courts, it is to the trustee his tutor, whom he is obliged to address and he must be silent, if this appointed protector judges that he has been treated too little for it to be worth talking about. He is attached to the engagement house as the slave used to be; it is not open to him to cross the limits even during his hours of rest, even on public holidays, without written permission from the operator, failing which he is arrested by the first police officer or gendarme who meets him and brought back to the house … as a criminal. “

Spare the negroes.

“They are so cruelly treated that it would be better to be a slave among the Turks” wrote Fr. Brunetti as early as 1660: “among the Turks”, “in Barbary”, let us understand among the Muslims. Through a religious connotation, this leitmotif of the 17th century expresses the height of misfortune. Purchase and sale, excess work, bad food, blows, repression of marronnage, mortality, worse still, cutting back at the level of the negroes and even below, because these are more precious. Without being expressed in the same form, we find this concern of “sparing the negroes” in the second half of the 18th century. At that time, questions about the possibility for Africa to continue to supply as many slaves as before would push for a resumption of the use of white labor. Designed in this spirit, the colonization of Kourou ended in resounding failure. At the same time, the great works of Fort-Royal were carried out by soldiers with considerable mortality. Thus, while the decision of the Council of State of September 10, 1774 ratified the end of the white recruits, the captains had to transport soldiers or workers to their places.

Transportation.

The chroniclers of the beginning of colonization blamed the conditions under which transportation was done. Father Du Tertre shows the recruits exhausted and decimated by the miseries suffered during the journey. As it can be exceptional trips, we rather retain the example of La Petite Notre Dame of 80 to 100 tons, left on April 28, 1635 bound for Saint-Christophe, that Jacques Petitjean Roget evokes in The Housing Company in Martinique. Half a century of training (1635-1685).

In this trip without drama, we notice Jean Du Pont, whom D’Esnambuc will place a few months later at the head of Martinique. This colonist, already installed, only brings back three hired men, but in total, we have 40 sailors and 94 passengers, masters or servants, that is, at best, 134 people for 100 tons. In other words, a crowding comparable to that practiced on most slave ships, even if some go up to two slaves for a barrel. According to J. Weber, in The last treaty, in 1854, for a journey, it is true much longer, the Augustus, of 300 tons, which left Pondicherry with 317 immigrants, triggers a scandal. Among the elements questioned, he notes the overload. The fact remains that, between slaves and engaged, the psychological conditions are not comparable during transport, even if the mortality is high.

Mortality after landing.

Mortality is also very high in Martinique. Between 1700 and 1702, the administration used 45 Limousin masons for the work of the fortifications. They arrived at the beginning of 1700 for St Christophe, but in 1702, the intendant Robert spoke of the work they carried out in Martinique. At the end of their three years of engagement, 10 died. This considerable rate of 222 per thousand for the three years, gives an average of 74 per thousand per year.

In the 19th century, commitments were made for five years: in Martinique, on January 1, 1856, the administration recorded 1,564 immigrants from India. As of December 31, 1860, there were 7,416. In five years we introduced 7,276, and repatriated 156. If we add 364 births, the total remaining should have been 9,204. As 1,632 deaths were recorded, the mortality rate was 147 per thousand for five years, an average of 29.4 per thousand per year.

Food and care.

Food and lack of care are accused of explaining the high mortality of the 17th and 18th centuries. This is found with slaves, but it also characterizes all newcomers, for example soldiers or sailors in transit, yet the object of all attention, and for whom the royal administration maintains hospitals. {mosimage} In 1680, Governor General Blénac blamed food consisting entirely of cassava and three pounds of stinky beef per week. Have there been any improvements? In 1700, the order of the intendant Robert on the engaged, which will be resumed in 1716, recommends 4 pots of cassava flour – close to eight liters – or equivalent in cassava per week, 5 pounds of salted beef, herds , and the sick employee must be treated and not dismissed. However, the edict of March 1685 grants to the slave of more than ten years only two pots and a half – close to five liters – of cassava flour, or three cassaves weighing two pounds and a half at least – therefore one total of seven and a half pounds, plus two pounds of salted beef, which can be replaced by three pounds of fish, almost half as much.

Comparisons with free workers allow better judgment. Thus, in the regulation of the lieutenant general of Tracy, “touching the blasphemers and the police of the Isles”, of June 19, 1664, the workers then being paid in kind, “their food and their wages were then regulated in the fashion of the country, namely six and a half pounds of cassava, seven pounds of meat, half beef, half bacon, a pint of brandy -near a liter- twenty pounds of petun per week. “The quantity of cassava is more low, but the worker catches up on the meat insofar as he receives nearly 50% more than the worker, and more than triple what is offered for slaves. It can resell, as we assume for tobacco. However, already in 1660, the allocation of slaves on Saturday reduced the cost of their maintenance to nothing, or almost.

The whip.

The subjugation of the worker to the whip or the stick, like the slaves, is certainly hard felt. However, we must limit the psychological consequences of this form of repression insofar as it also concerns free workers.

The law reinforces usage. In 1664, article 8 of Tracy’s regulations defended “all European and Negro commanders from poaching negresses, barely twenty shots of liana by the master of works for the first time, forty for the second, fifty and the fleur-de-lys marked on the cheek for the third, without this article deviating from what is practiced in the island at regard for civil interests on such an occasion. ”The same penalties are applied“ against the other valets de case who have lived with negresses ”. The masters were not sanctioned until the Baas settlement of August 1, 1669, which threatened them only with financial sanctions.

In 1666, a regulation of the Council of Martinique and an ordinance of the governor general affecting the workers strengthen the powers of the employers:

“On March 2, 1666, the Council made a regulation concerning all kinds of workers, particularly masons and carpenters, because of their high cost, their insolence, their laziness (…). They are ordered to start a quarter of an hour before the sun rises and to finish a quarter of an hour after the sun has set. (…) They are forbidden to make mutineers and insolent in the inhabitants where they will work; allowed in this case the inhabitants to chastise them like their working people, with forbidden to said workers to replicate and stop their work until they are finished, and in case they are found defective, they will be mended to their costs. “

Whether regulatory or not, these practices are confirmed by employees who had a sufficient level of culture to write it: Guillaume Coppier, in 1645, in his History and trip to the West Indies, or the surgeon Oexmelin, led to Île de la Tortue, near Saint-Domingue, in 1666. Employed first as a farmer, he then worked for the governor before going on a race with filibusters, and in 1688 published a Histoire des aventuriers which have stood out in the Indies with the life, the customs, the customs of the inhabitants of Santo Domingo, allowing us to summarize the essential of what has been said previously:

“As soon as the day begins to appear the commander (in Martinique, it would have been said: the commander) whistles so that his people get to order; it allows those who smoke to light their pipes and leads them to the work of chopping wood or growing tobacco. He is there with a stick called a liana; if someone stops for a moment without acting, he strikes it like a galley master on convicts (…). Whoever is in charge of cooking cooks peas with meat and chopped potatoes as turnips? When his pot is on fire, he will work with the others; and when it’s time for dinner he comes back to cook it As soon as we have dinner we come back to work until evening; and we eat as we ate dinner; then we take care to trim the tobacco, (to remove the large veins) to split the mahot which is a tree bark suitable for binding tobacco (…) ”.

Like Father Du Tertre, in 1667, or Blénac in 1680, Oexmelin also evokes the blows given to push the sick employees to work. The latter was fortunate to be bought by the Governor of the Tortoise who needed his services. Others seek their salvation in flight.

The marronnage.

The texts cited for the 17th century do not raise the issue of marooning. Nevertheless, the officials concerned about it from the first days of official colonization, we can think that the flight is as old as the engagement. In this area, the engaged are constantly put on the same footing as the slaves. This is already the case when article IV of the agreements signed between D’Esnambuc and Warner on May 13, 1627 states that: “The said governors may not remove any men or slaves from their dwellings which will not belong to them, thus (but) will remain seized of it until they are given notice of said men or slaves. ”These agreements were renewed in 1638, 1644, 1649 etc.

Very explicit, that of 1654 separates free people from servants or slaves who always find themselves equal:

Art. VII. “That if some servant or slave escapes from his master, and retires to the other nation, and it is sufficiently proven that he was employed more than twenty-four hours by no inhabitant, or sent out of the ‘island, the said inhabitant will be liable to his master for all damages …’. Art. VIII. “That no man, although free, of the two nations, will not be retained by any inhabitant of the other, to work, without passport of the governor of the nation where he lives (…)”.

Passports and tickets do not stop the desire to work freely, because of those who seek to take advantage of the labor of others at a lower cost, as noted by Du Parquet and the Sovereign Council created in 1645: “Daily negro slaves, and even French servants, make themselves brown and are taken or arrested by other inhabitants who, instead of having them published incontinent and expose them in public to be recognized, withdraw them from their homes, make them work for their own profit, and by succession of time take possession ”(…). Some servants “pretend to be free”, too, “in order to prevent French servants who make themselves brown, (and) all negroes from surprising the inhabitants on the pretext that they say they are free. We have ordered that in the future no servant be received in the residents’ hut unless he has a ticket from his master, containing that he has had his day (…) so that he is encrypted us. “

The sale.

Until the sixties of the seventeenth century, most of the contracts were signed between people who knew each other, or for a specific hire agent represented by an intermediary. From this decade, the engagement becomes more and more a business led by merchants who entrust the hired to a ship captain. On arrival, the latter being obliged to sell his passenger to the first comer to recover the costs, the institution becomes dehumanized.

In his analysis of the royal ordinance of 1716, Dessalles does not speak of herds, but retains the prohibition to desert, to maroon. At the time of Sch ÷ lcher, nothing has changed, nor is it slavery, but the margin is all the narrower since the Africans were bought before being liberated in law and, in some so, enslaved to commitment.

From boom to decline in engagement.

Whatever the opinion aroused by the accumulation of negative images that we have just offered, it is however when they are the most unsustainable that the committed flock. G. Debien, who studied 6,200 Rochellais contracts, observes a clear decline at the end of the eighties of the XVIIth century. However, more than a quarter of the contracts were signed between 1660 and 1665, in just six years out of the eighty studied.

In Martinique, in the XVIIth century and at the beginning of the following century, even if certain servants were no longer engaged, they are likely to have been because, between 1660 and 1732, the counts sometimes counted the servants, sometimes the Engaged whites, or engaged and domestic workers. The nominal counts of 1664 and 1680 are incomplete and not all companies have sufficient information. However, they allow us to assess roughly two-thirds of the population.

Thus, in 1660, for 721 huts – elsewhere we would have spoken of fires – we counted 559 servants, that is more than one white in five, and a little less than five slaves for a white servant. The maximum was reached in 1671 with 969 whites hired for 1086 huts. The recruits then account for a quarter of the Whites and there are, on average, about 7 slaves for a White engaged. Then the decay begins. In 1702, 149 in number, this group made up only 2% of the white population and we count 116 slaves for a committed white man.

In detail, certain fluctuations are due to the great conflicts which engage the maritime powers: war against Holland (1672-1678), war of the League of Augsburg (1688-1697), war of the Spanish Succession (1701-1713 ). The embarrassment brought to navigation, therefore to production and trade, plays a role in the cyclical decline of engagement because peace brings up the figures and the percentages.

Thus, during the last 6 months of 1717, 203 recruits arrived in Martinique. In 1719, the 490 engaged or domestic workers represented 5% of the white population and each had no more than 72 slaves in front of him. But, in 1732, we have already fallen to 362, or 3% of the white population and 126 slaves for an employee or servant. On this date, we must bring in explanations of a demographic, economic, or negative image type, to the extent that the immigration of the previous decade has, in part, served to fuel piracy.

As early as 1680, Blénac explained the decrease in the number of recruits by that of the white population attracted by the “libertinage of the coast of Saint-Domingue”, in other words, the flibust. Behind this attraction lies the non-value of tobacco which has prompted many small inhabitants to sell their land to sugar bowls. The “peoples” being too poor to pass on recruits, the governor general proposed, in vain, that the state intervene by granting fiefs to important people who would pass “100 men during the year”.

From the allocated to the committed: from the private contract to recognition by the State.

Blénac’s proposal suggests that if the development of state intervention in social matters, what we can call social absolutism, comes at the expense of private initiative, it is because the administration is trying to counter an evolution which it considers negative. Rent companions, allocated, are the first terms which distinguish certain men from the crew and people embarked on their personal account by passengers. Without being able to exactly date the beginnings of these contracts, we note that they were initially only private law, and that the first known in France would have been signed in 1611. The practice is well established before the beginnings of official colonization of Saint-Christophe in 1626, as well as the French practice of the duration of three years. Compliance with this clause has never been absolute. However, it is after the official recognition of the engagement, and at a time when the entrants are numerous, that we register protests over the duration. To maintain white immigration, state intervention has two objectives: one humanitarian, the other security, but no legislative provision will prevent the institution from declining.

According to Jacques Petitjean Roget, in Saint-Christophe, premiere of the French Isles of America, in October 1624, “Six men, all Norman aged 19 to 20 years admit” having submitted and obliged “to Pierre GOURNAY, bourgeois from Le Havre , leaving on the ship of Georges de NAGUET “” to go to the islands of Martinique, Dominica and other suburbs “, where the engagiste claims” to take up residence for three to four years to navigate and traffic all kinds of goods (…) to garden in said places to make petun ”. The salary of the allocated is between 30 and 45 pounds tournament per year, plus food. Here, it seems that the questions concerning clothing, care and the return journey are not mentioned because they are implicit.

The multiplicity of types of contracts creates various types of employees. G. Debien in Les Engagés pour les Antilles (1634-1715), distinguishes a group formed by support or travel contracts. In this case, a worker will exercise his trade by signing what we could today call a fixed-term employment contract with a well-defined employer. A close type is the association contract. Fewer, and later, are the contracts of hunters, buccaneers. Equally rare are apprenticeship contracts. Paid only in kind, and generally after three years, with no guarantee of return at the expense of the operator, the bulk of the recruits is increasingly made up of emigrants who do not know who will buy them, or whether they will be sold after a first purchase, which introduces additional elements of comparison with slavery. For the most part, with or without previous qualifications, like Oexmelin, they will work in agriculture.

The recognition of the commitment by the State is done first indirectly, through the Compagnie des Iles d’Amérique. Thus, the commission given on October 31, 1626 by Cardinal Richelieu to the Sieurs D’Esnambuc and du Roissy states:

“That no one is received to go to the said enterprise unless they oblige themselves before the said lieutenants of the Admiralty or other judges in their absence, from the places where the said embarkations will take place, to stay three years with them or those who will have charge and power of them to serve under their command (…) ”.

In February 1635, by article 6 of their contract, L’Olive and Plessis promised to pass only French and Catholics, “and all will serve three years”. This clause is not always respected. Still thanks to Father Du Tertre, we know both reactions which would have been terribly sanctioned among slaves, and one of the regulations made in favor of the hired before 1667, date of the beginning of the publication of his General History (… ):

“Around the year 1632, the prudence of Monsieur D’ESNAMBUC appeared in an extremely unfortunate encounter (…) Several officers and some of the wealthiest inhabitants had maliciously hired all their servants without their knowledge for five years, at the imitation of the English who usually hire their own for six or seven years. Most of these poor hired workers, seeing that after four years of service there was no talk of giving them leave and that they were not allowed to work for them, began to complain, to make tumultuous assemblies, and as their number was greater than that of their masters, and that they were not less valiant than them, the majority having carried the weapons, one spoke nothing less than to make the servants masters and the masters servants so that the colony (…) was on the point of destroying itself (…). M. D’ESNAMBUC (…) saw them on the point of ending their dispute with iron and murder (…) he satisfied them all; ordering that all the servants who had completed their three years of service would have their freedom, in accordance with the establishment of the Company (…) “.

At the end of the century, Father Labat criticized the British example even more severely: “Their workers are in large numbers (…) the greater part are poor Irish people, abducted by force or by surprise, who groan in a a hard bondage of at least seven or five years, which they are made to start again when it is finished, under pretexts whose masters have ready-made provisions. ”

Let us beware, however, of chauvinism at a time when England is the hereditary enemy, since these words seem to lend extraordinary longevity to those who work for the British. France also had its deportees, for example, Protestants in 1687. Contrary to what happens in the British colonies for Irish Catholics, very quickly, the other Protestant deportees were no longer placed as engaged. The state also dispatched women and girls in the 1980s to marry them. We also note in the eighties of the XVIIth century, and at the beginning of the reign of Louis XV, a small number of galley slaves very badly received by the owners. Weren’t there any hints of committed-galley assimilation? By bringing together 76 committed and galley slaves in the same chapter, the census of 1689 puts us on this path.

Locally, one can find some condemnations to the engagement. In 1666, Governor Clodoré condemned 15 seditious people to serve the Company without wages. In 1671, considering that “several young libertine men, without vocation and without confession lead a scandalous life (…) poach young Creole children from the islands and make them abandon the work of their homes and the cultivation of the land, to follow their vicious inclinations “, the Superior Council of Martinique condemns two men” surprised by committing infamous actions “, to 18 months of engagement with very determined owners. Actions not specified, but judged contrary to the rules of good life and manners.

Léo Elisabeth